Terri is co-founder, webmaster, and editor of The Hyacinth Review.…

In 1988, five children were abandoned by their mother in a small apartment complex in Tokyo, Japan. The children lived alone for over six months, surviving on the ¥50,000 (USD $350) that their mother had left them before running away with her new boyfriend. The children were later discovered and their mother brought to trial, but by this time the youngest two children had passed away.

This disturbing case, known by Japanese officials as the “Affair of the Four Abandoned Children of Nishi-Sugamo,” gains further public awareness in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s haunting docudrama Nobody Knows.1 The film follows the children as they try desperately to survive in their unthinkable situation, and Kore-eda draws the viewer into each scene both visually and emotionally through the use of color and symbolism in a dreary Tokyo setting.

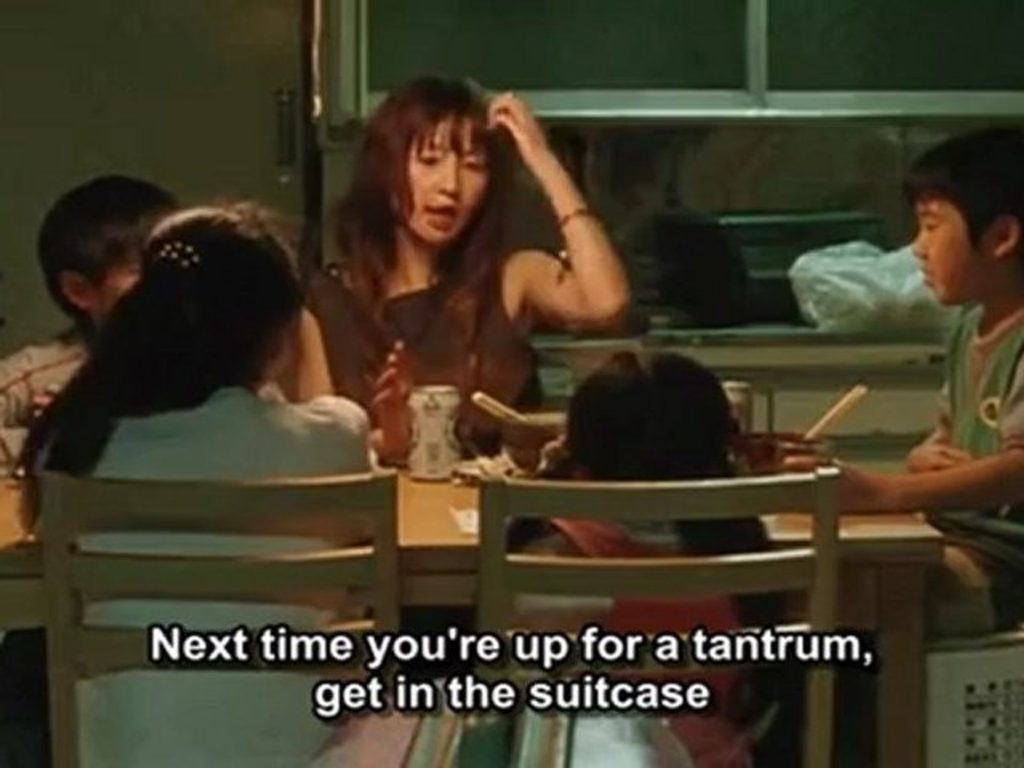

Nobody Knows opens as the Fukushima family moves into their new apartment. Keiko and her son Akira greet the landlord, and she makes a point of noting that he is an only child with a father away on business. However, as the film progresses we see that Keiko has managed to sneak in three more of her children and, as they sit around the dinner table – her children literally looking up to her with the ever-present suitcase in the foreground – she gives them a review of the rules of living secretly in their new home.

We are then shown what life is like for the four children while their mother is away at work. Akira is allowed to leave the apartment to purchase groceries and other essentials, while his sister Kyōko stays at home and does the family’s laundry on the balcony after making sure that no one in the neighborhood can spot her. Shigeru and Yuki, the youngest children, pass the time with toys and coloring books as the two oldest prepare dinner and wait for their mother to come home. Each day in their life is a carbon copy of this routine, but one morning after a series of drunk nights and absent days, Keiko leaves her children for months, then forever.2

The film is tastefully done and the plot maintains a sense of reality while engaging the viewer in an almost fairytale-like series of events. It is a child’s world, albeit a grim one, and in this vein, Kore-eda includes a subtle symbolism. While the atmosphere of the film is eerily calm and both the soundtrack and scenery lightly muted, there are several instances where bright red objects come into play.

The color red harbors a variety of symbolic meanings including danger, passion, and anger. In many cultures the color red is considered to be good luck, however, in the context of this film, it seems that the unique presence of several red objects represents transition and change, as well as frustration.3

The first red object that the viewer might notice is the suitcase in which Yuki is smuggled into the apartment. Yuki is introduced into the story upon exiting the suitcase, and she is placed in it upon her burial in the airport field. In this sense, Kore-eda transforms the suitcase into a womb-like symbol; it represents all that her mother cannot – stability, comfort, and a place of safety when she is feeling sad – as well as everything that her mother forces upon her – change and confinement.

Yuki returns to the suitcase when her mother is away, further cementing its place as a symbol as the surrogate provider. It comforts her when she is worried, and it is always there throughout her day as she plays nearby in the cluttered apartment.

One reviewer mused that it is through this cluttered apartment that Kore-eda creates “a sense of intimacy,” shooting close to the children and underlying their “claustrophobic imprisonment”.4

Another prominent red object in little Yuki’s life is the red, strawberry-patterned box of Apollo Choco candies. Yuki asks Akira for these before he leaves the apartment, she eats them on her birthday, and she is buried with a dozen after her death. The candies strongly represent childhood and innocence; the box is lined with a small cartoon, and the inexpensive nature of the candies makes them easily accessible to children – or at least children with spare pocket money. They are something that can only be obtained from the outside world – they are a symbol for the childhood that she should have access to, but is cruelly cut off from.

The viewer is also introduced to the crimson bottle of nail polish that Kyōko interacts with throughout the film, much to her mother’s chagrin. When Kyōko expresses her desire to go to school, we see a close-up of the nail polish bottle for the first time. Later in the film, the last time her mother is in the house, Kyōko spills the red polish on the floor. Kyōko interacts with the nail polish in a way that implies a longing for the life outside of the apartment she shares with her family. She continues to play with the bottle despite her mother scolding her over going through her possessions and in this way the nail polish bottle symbolizes the normality of a life that Kyoko and her siblings can never have.

Though they are still children in many ways, they are never allowed to fully express the joys, mistakes, and experimentation of the self that comes with childhood, and the nail polish serves as a way for Kyōko to step back from the homemaker/caretaker role she was forced into and play make-believe for a while.

In contrast, the nail polish also has the potential to symbolize the paradoxical childlike womanhood that Keiko lives. Her refusal to allow Kyōko to play with the polish is similar to that of an older sister – greedy and boundary-oriented, quite unlike the nurturing ways of a mother easing her daughter into the trials of womanhood.

There is also a scene later in the film in which the focus is placed on a red flowering plant in an abandoned lot which Shigeru and Akira collect the seeds from the plant during the children’s outing. They continue to collect a variety of seeds and plants, as well as soil, in order to grow them on their balcony.

It is not entirely clear whether the plants are grown as a food source or merely as something for the children to look forward to – either way, the introduction of the red flowers represents a turning point in the children’s lives, during which they decide to break free from the rules and consequences that their absent mother set for them and become even more self-sufficient than they had been in the past.

While there is a multitude of other colors and objects in the film, none are as eye-catching as red in a world of muted tans and grays. It is the presence of these particularly prominent objects – the suitcase, candy box, nail polish, and flowers – that gives Nobody Knows its ominous fairytale-like quality. In a dull, eerie, and perpetually lonely reality, the occasional brightness of a notable object is somewhat reminiscent of a story straight from the Brothers Grimm.

Snow White had her apple, Cinderella had her shoes, but unlike a fairy-tale, Nobody Knows lacks any semblance of a happy ending, and this – along with the viewer’s knowledge about the truth and reality of the situation – is what makes it such a haunting, resonating film.