Terri is co-founder, creator, and editor of The Hyacinth Review.…

Between 1846 and 1874, Margaret Dickinson collected and illustrated over four hundred and fifty plant specimens from sources across the British Isles.1 Though little else is known about Dickinson’s life, she is now widely cited as a naturalist, botanist, and illustrator – titles she did not possess during her lifetime.

Due to its peaceful and “simple” nature, the study of plants was initially regarded as a feminine hobby, and it was not until the work of well-respected botanists Joseph Hooker and John Lindley that botany was recognized as a true science.2 As such, the serious study of plant life was overlooked in pre-Victorian England and much of the historical information on botany from this time comes from the collections and notes of women who, much like Dickinson, took their botanical pursuits to a higher level.3

However, views on botany changed through the introduction of the tropical orchid, and the act of studying the plant kingdom was transformed from a leisurely, feminine pastime to one with “serious” scientific potential.

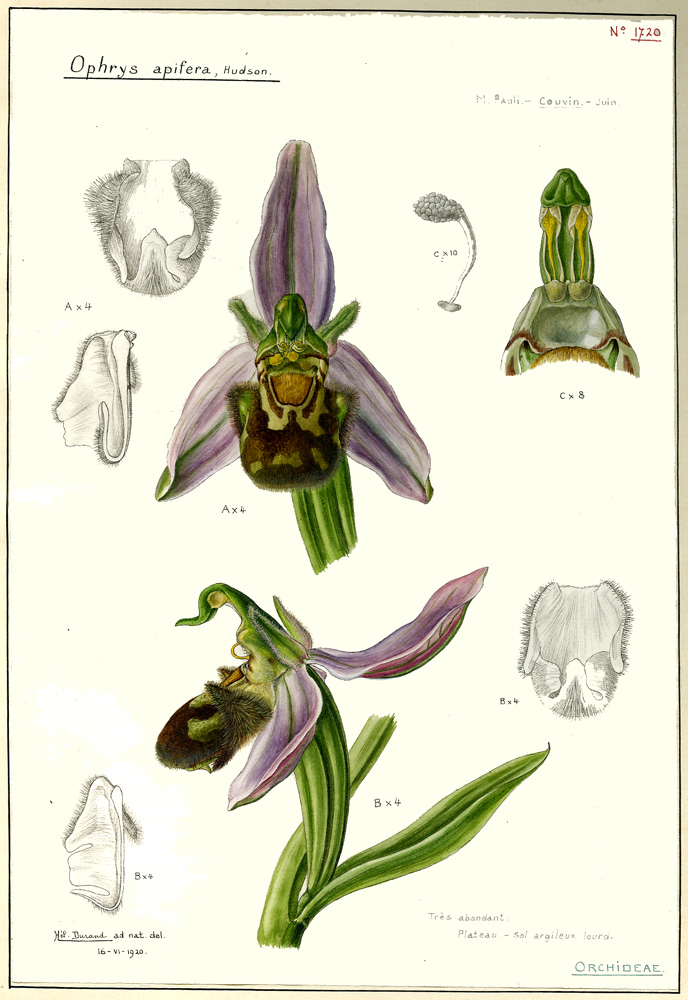

While horticulture had its place in pre-Victorian England, it wasn’t until the arrival of the first tropical orchid (an unnamed lavender member of the genius Cattleya)that Victorian England took a serious interest in botany.45 Unveiled to a public familiar with the blooms of countryside orchids such as Ophrys apifera, commonly known as the ‘bee orchid’, the exotic blooms of the new arrival garnered serious public appeal, sparking the cultural phenomenon now known as “orchidelirium”.6

The introduction of this unique specimen initiated a new obsession in the Western world, and orchids were sought after with intense desperation and enthusiasm that reached all the way to Queen Victoria herself.2 However, orchidelirium quickly proved to be deadly.

The orchid enthusiasts of Victorian England were under the false impression that growing orchids was a challenging task, which resulted in the ecological destruction of the orchid’s natural home, the exploitation of native populations, as well as an increased value on any orchids strong enough to have survived these horticultural oversights. Assuming that orchids required steamy, dark environments, the plants were often grown in “stove-houses” in which fires were kept burning constantly and little light was provided. In actuality, orchids require well-circulated fresh air and varying levels of sunlight.5

Still, despite the obstacles, the progress of orchid culture and study maintained a steady course, with many notable individuals of the time falling victim to orchidelirium, including Charles Darwin who, in January 1862, wrote a letter to botanist Joseph Hooker thanking him for sending a specimen of Angraecum sesquipidale.7

Intrigued by the unusual length of the flower’s spur, Darwin predicted that it could only be pollinated by a moth, one which would have co-evolved alongside the flower due to its equally long proboscis.7 Forty one years later, Darwin’s prediction came true, and a subspecies of African hawkmoth, Xanthopan morganii praedicta, was confirmed to be the pollinator of its partner plant.

The orchid family’s tendency to have specific pollinators and evolutionary partners made it the perfect subject for Darwin to explore for his work on adaptation, and in May 1862, five months after receiving a specimen of Angraecum sesquipidale, Darwin’s Fertilisation of Orchids was published.78 The work focused on a variety of orchids and the distinct characteristics which enabled their pollination by specific organisms.

It is here that a literary-critical perspective is important, as Darwin’s writing on the subject is specifically laid out in order to appeal not only to professional botanists but to a general audience who, presumably, would have little background knowledge on the scientific aspects of the family Orchidaceae.

In its first chapter, Fertilisation of Orchids provides an overview of the orchid itself, as well as the various insects that, at the time of publication, were known to have been common pollinators.8 The book then goes on to discuss the genus Ophrys in terms of structure, means of fertilization, and differences in flower shape. It is notable that Darwin begins with an analysis of this genus as one of its members, Ophrys apifera, is one of the most recognizable native orchids in the British Isles and therefore would have stood out to a layman audience.

Having gained the reader’s attention, Darwin goes on to describe several other European orchids, and it is not until the fifth chapter that he begins to focus on more unfamiliar tropical orchids such as the genera Cattleya and Masdevallia.

Even within the chapters themselves, Darwin begins with the most notable flowers and moves on to more obscure specimens, careful to maintain a level of familiarity with the reader and conscientious of both their background knowledge and level of commitment to the subject.

The introduction of the tropical orchid in Victorian England was a doorway to the world of botany; one that has since led to countless discoveries in fields ranging from gastronomy to medical science.9 Due to its promotion by well-respected men of science, orchids gained prominence across social spheres which resulted in the heightened status of botany. It is uncertain whether or not the field of botany as a science would have progressed as rapidly were it not for orchidelirium and the subsequent global interest taken in orchids, but its influence is undeniable, and its effects are enjoyed to this day.

Terri is co-founder, creator, and editor of The Hyacinth Review. Currently based in Paris, she works as a writer, photographer, and freelance web designer. Her work has been published in a variety of publications including NME Magazine, Kanilehua Art & Literary Magazine, Hohonu Academic Journal, and The Euhemerist. Terri holds a B.A in English from the University of Hawai'i at Hilo, and spends her time exploring the arts & humanities.